“WPRB and Me”

[By Chris Fine]

LISTEN: Mic breaks and news reports from Chris Fine’s rock show on WPRB, February 25th, 1980.

Introduction

I write these words about WPRB because I love the station. The people of WPRB were some of my best friends during my years at Princeton. WPRB was the single best activity (including courses – as my transcript reflects) in which I participated during my undergraduate years. My interest in radio, and technology in general, dates back well before my journey to Princeton University in September, 1976. Encouraged by my father, who was an audio engineer and inventor, I started tinkering with electronics and chemistry at a young age. Predictably, a number of shocks and small fires resulted – but fortunately no major injuries, and my family was always patient with me.

My father was an avid amateur radio operator (aka “a ham”). He had had a license when he was a boy, but it lapsed during World War II. Dad claimed that the FCC had done him wrong by cancelling his license while he was serving in the Pacific and could not respond in time to the renewal notice. A long-standing grudge against the FCC finally dissipated by the early 1960’s, and my father renewed his license. He installed a high-end radio station in the basement of our big old family house when I was about 6 years old, and I was fascinated by it. I was dying to use it, and my father couldn’t have been more generous and encouraging. I got my first ham license when I was 12, followed shortly thereafter by the “Advanced” license that permitted operation on all frequencies except small slices reserved for the “Extras,” or elite-level hams, who had to pass a Morse Code test that was just too fast for me.

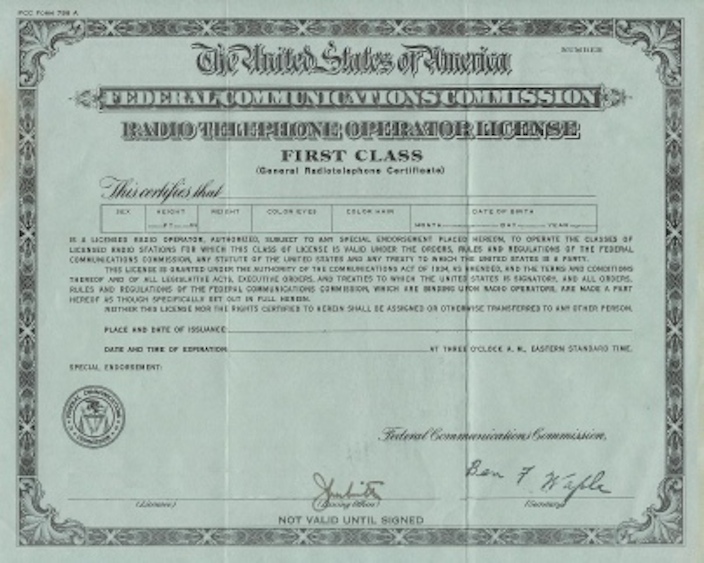

Prior to his military service, my father had studied to obtain the coveted FCC First Class Commercial Radiotelephone License. This was the big time; the “First” allowed a person to be a professional radio engineer, including building, installing, operating, and certifying broadcast equipment. When I was a boy, Dad used to tell me all the time, “Why don’t you get that ‘First’ yourself? They might draft you! If they do, you can be like I was – become a Technical Sergeant and operate radar or some other technology instead of being in the first line of infantry!” The Vietnam War was still active when my father started talking about this idea, as was the draft. Therefore, getting the FCC credential seemed like an excellent suggestion for enhanced survival odds. With my bad vision and general lack of coordination, patriotic though I might have been, my survival time in the “first line of infantry” would probably have been measured in minutes.

Prior to his military service, my father had studied to obtain the coveted FCC First Class Commercial Radiotelephone License. This was the big time; the “First” allowed a person to be a professional radio engineer, including building, installing, operating, and certifying broadcast equipment. When I was a boy, Dad used to tell me all the time, “Why don’t you get that ‘First’ yourself? They might draft you! If they do, you can be like I was – become a Technical Sergeant and operate radar or some other technology instead of being in the first line of infantry!” The Vietnam War was still active when my father started talking about this idea, as was the draft. Therefore, getting the FCC credential seemed like an excellent suggestion for enhanced survival odds. With my bad vision and general lack of coordination, patriotic though I might have been, my survival time in the “first line of infantry” would probably have been measured in minutes.

The Vietnam War had ended by the time I was 16, but there were always other conflicts, so I thought: I’ll be ready, and maybe this will get me a job, too. I studied hard for months, and passed the First Class exam. In those days, the exam comprised hundreds of technical and “rules and regs” questions, and took hours. The testing took place at the old FCC office in New York City, presided over by a gruff old fellow whom my father called “Grumpy.” (“He was at the same desk when I took the test!”)

Prior to WPRB, the First Class license was mostly a point of pride for me, and led to neither income nor a military assignment on a balmy island full of advanced technology equipment and visiting nurses. (That was my father’s description of his wartime assignment. I later found out that the island had been infested with pests, sporadically bombed by the enemy, and surrounded by a reef which emitted so much toxic coral dust that my father was forced to accept a medical discharge from the service.)

Prior to WPRB, most of my interest in radio was technical. Although I loved music, listened to the New York FM rock and jazz stations, and collected historical radio broadcasts, I had paralytic mic fright and thus, even as a ham, hardly ever spoke over the air, preferring to communicate via Morse code or radioteletype. I could barely even bring myself to talk on the telephone.

The Arrival: Discovering WPRB

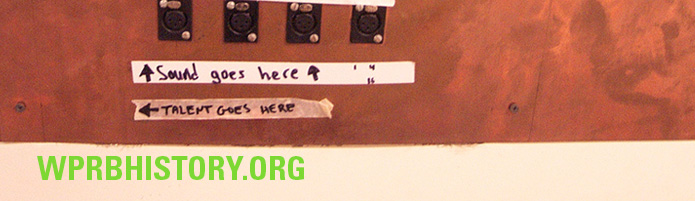

So it came to pass that, near the end of Freshman Week, I found myself in a line of people squeezed into a doorway leading to the basement of Holder Hall. The person in front of me in line was David Holmes ’80, who became a close buddy during the undergraduate years and a lifelong friend. We met while waiting to descend the dank stairs into the cramped WPRB quarters, to meet the WPRB staff and check the place out. Upon entering the studio area, I fell immediately in love with the idea of working there. The equipment was fascinating to me, as was the whole concept of a “real” radio station operating in the commercial band! The dark and cluttered “Tech Shop” would become a second home. The staff seemed welcoming and actually talked to us freshmen in a warm manner.

[Holder Hall image by Peter Dutton. CC BY 2.0]

Upon inquiring as to who was on the engineering staff, I was introduced to Glenn Bishop ’77 and Martin Pensak ’78. Glenn and Martin were, at the time, the only known holders of FCC First Class licenses on campus. (It turned out that there were a couple of others, including Mark Greeley ’78, who later became active at WPRB – but they hadn’t surfaced at the time.) Until many years after I graduated, any commercial station required at least one “First” on staff or on retainer, to maintain and certify the transmitting equipment. Now I was the next licensee to show up – the heir apparent. A-ha! At last! The big FCC exam had delivered a golden opportunity to me.

I couldn’t wait to begin.

From Apprentice to Chief Geek – The Technology of WPRB, circa 1977

I started out by working on the transmitting equipment and studio gear with David Holmes, Glenn Bishop, Martin Pensak, Joseph Levitsky ’80, and a couple of other technical types. At the time, WPRB’s transmitter and antenna were located in the tower at the corner of the Holder complex. The transmitter was near the base, and the antenna was at the top of the tower. The transmitter was a 20-kilowatt Collins unit. In many ways, it really was a beautiful piece of equipment, as was almost everything that Collins Radio made. However, it occasionally became finicky. When that happened, all bets were off. Maintaining the tubes in good order and adjusting various things tended to keep it on the air for my freshman year, most of the time. Summer after freshman year, came a crisis (which we’ll get to shortly). The antenna never gave any trouble. I liked to climb up on it when the transmitter was off – the view was gorgeous, even at night.

The studio equipment was more problematic. The main control board was a Collins unit, of advanced technical design. The key advance was the use of optically-coupled volume controls, rather than the traditional wired “pots.” The theory was that the optical system would eliminate hum and noise, the twin plagues of old-school consoles. Generally, this was the case – but the complexity of the optical system caused endless headaches, including burnt-out bulbs that were buried in the innards and hard to replace. I remember laboring over that board many a night, alone and with others, trying to get something working.

There was an older board (probably the Gates unit that the Collins had replaced) in another studio, as I recall. It crackled and hummed regularly, but not so badly as to trigger a crisis. If you listen to advertising spots and PSA’s from that era, you can hear some of the artifacts, as that studio was used for production of recorded material.

The station control apparatus was an automated switching system built from surplus telephone equipment, allegedly by David Boggs, who went on to global fame as the co-inventor of Ethernet at Xerox PARC. All I know is, we rarely had to mess with it or do much switching, which was a Good Thing because there is no telling how we would have fixed it if it had broken. In theory it was capable of switching all operations over to a backup studio in a seamless manner. The hand-drawn wiring diagrams of this system alone were labyrinthine. We rarely tried to push our luck and activate the system.

The various reel-to-reel tape recorders and cartridge tape machines were in various states of repair. Charitably, I would describe them as “tired but faithful.” They were used extensively in all operations. The station only had enough budget to buy one every so many years. The newest one was a Scully unit that pre-dated my tenure by a couple of years. Periodically we would clean and align the heads, fix burnouts, etc.

Midway through freshman year, I was honored to be named Chief Engineer for a year’s tenure. That meant: Something breaks, it’s you, Chris! And I had to sign all the transmitter logs every week. All of this was absolutely OK with me. I loved it.

First Time on the Air: Accidental and Exciting

As I mentioned, maintenance was performed late at night. On most days, WPRB ran a 24-hour schedule – at least, they did if they could rustle someone up for the graveyard shift. The 10PM to midnight shift most nights belonged to a campus group who did not take kindly to a lone geek shutting them down precisely on time on maintenance nights. To their credit, they never caused me any difficulty, but at first it was intimidating for me as a young, timid engineer, to walk into a totally dark station, but for the indicator lights, with fragrant smoke wafting on the studio breeze, to say, “Er, sorry, fellas, I have to work on the transmitter!” I had no concept of what “cool” was.

One night in the spring of 1977, it came time to put the station back on the air, at about 2AM. Normally, I would just switch on the transmitter and put on a station ID and PSA to test the audio, before shutting down the transmitter again after all measurements were complete. This time, though, I had been doing some work on the Orban OptiMod exciter we had (credit to Bob Orban, audio genius and Princeton graduate). I needed to run some more audio and monitor it. What to do? I was panic-stricken. But… who would be listening? Why not try? I got on the air with no training, made at least 100 mistakes in the first 30 minutes, and absolutely loved it. I invited my friend to come over, and we clowned around for a while. I still have a tape of it – under lock and key in the “embarrassment vault,” of course.

The spring schedule was booked up, but I knew – as of sophomore year, I’d be on the air!! I probably sounded terrible, but they basically had to give me something because I had the First Class license and they needed me to certify the equipment.

Anecdote: “Relativity Radio Theatre”

During the spring of my freshman year, WPRB broadcast an excellent series of classic science fiction dramatizations, initially called “The E=MC Squared Radio Hour,” and subsequently, after a listener contest to find a new name, “Relativity Radio Theatre.” The show was sponsored by a comic-book store in town called “E=MC Squared.” Some of the shows featured episodes of “X Minus One,” an amazing show from the 1950s which dramatized famous sci-fi stories. Other shows featured recordings of celebrities, such as William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, Vincent Price, and David McCallum, reading stories. Occasionally, the host, Rob Gross, would throw in a classic tune like “Flying Purple People Eaters.” There was a loyal audience, a generous sponsor, and all was well.

Until, that is, one night when WPRB broadcast a record featuring Harlan Ellison performing a spirited reading of his short story, “Shatterday.” I’m still not quite sure why nobody had listened to the record in advance – but “Shatterday” featured some extremely choice language at various points. The first time the F-bomb went over the air (I still remember the line: “Jesus Christ, you’re out of your F*** mind!”), panic set in. What should we do?? We had no tape delay. In those days, the FCC could – and would – fine or take off the air any station broadcasting far tamer language than Harlan was passionately declaiming.

So here’s the story: Nobody did anything. We had a hasty series of telephone calls with station management, and everybody agreed: The Show was Just Too Good! We were too into the story. The managers let it fly, and the show was a huge success. We never heard from the FCC, either. Fortunately.

I still have the recording.

Tech Trivia: The AM System

I’m not sure who remembers this, but WPRB actually started as an AM station, using a transmission technique called “Carrier Current AM” – aka, “how to transmit when you don’t really have a full license.” It was perfectly legal. Carrier current worked by using the power wiring in the dorms as an antenna, transmitting very low power AM on the broadcast band. Though the station had long turned to FM, and its coveted commercial frequency slot, by the time I got to Princeton, the AM system was still running… sort of. For some reason, we were supposed to keep it going. It was a real headache. Wires ran everywhere, and the ancient transmitter units were unreliable. The signal was tough to pick up, even with a good radio.

When did they turn it off? I don’t know if anyone was listening to the AM signal in the 1970s, but for some reason, somebody wanted it kept on.

Summer 1977: The Great Transmitter Fire and the Northeast Blackout

During my undergraduate summers, I had an internship at IBM. I’m not quite sure why I got it, since, in theory, I was at the bottom of every preference list for summer hiring. Maybe I was just lucky. It was a full time job, paid well, and I learned a lot.

The very best thing about the summer of 1977 was that I was doing a part-time engineering/broadcasting gig for WPRB. I didn’t live too far away, and would go down on Saturdays to do a show and check all the equipment, and to certify the transmitter logs. It was such a treat – the beautiful campus, the beautiful weather, cheesesteak sandwiches, and radio! I’d bring friends, we’d hang out, and it was great.

The gig did come with responsibility though – if something broke, I’d get the call. One day I was at work and my mother called me to say that John Shyer ’78, the Station Manager of WPRB, had called, and advised to call back urgently. When I called back, John told me (in his magnificent stentorian voice) that WPRB was off the air! There had been a minor fire in the transmitter and they needed me right away.

I talked to my boss at IBM, who, fortunately, was an understanding person, and I then promptly ran home to pack and drive down to Princeton. Over the next couple of days, those of us who were there worked feverishly to fix the damage and locate a new circuit breaker, to replace the main breaker that had burned out. On the evening of the second day, the part arrived and I installed it. Everyone stood around holding his breath. I switched it on and Clunk! The breaker snapped off again.

We were in a state of despair. We couldn’t figure out what was going on. That was when I learned a life lesson: Always check the part number! We finally located a nearby professional broadcast engineer and Collins service professional, who agreed to stop by. Within minutes, he noticed that we had installed the wrong part. Collins had sent us the wrong part. Our friend located a used part, which we were able to install until the correct one arrived. We were back in business. When I got home, my father looked at me with complete exasperation, as if to say, “My son, the engineer – he didn’t look at the part number!”

Later on that summer, I was home one evening, sitting on my parents’ front porch in Westchester County, NY. It was a night of thunderstorms, and I had an eerie feeling. As it happened, my parents were traveling. My next-youngest brother was out for the evening (he always had a date, which I never had at that point). I was watching the two youngest brothers, who had (more or less) gone to bed. Suddenly, the streetlights started flickering. They came back for a few seconds, then went out, along with all the lights everywhere I could see.

We had a battery radio, and I tuned in to WCBS-AM. It quickly became apparent that a massive blackout was in progress. My two youngest brothers sprang out of bed and prepared for an evening of unscheduled fun. My next-youngest brother drove home, after reporting that the lights had gone out in the middle of a movie and were out everywhere. Unable to capitalize on what might have been a golden opportunity, he had dropped off his date. I then drove around the neighborhood, experiencing the ghostly darkness.

Of course, in the middle of this crisis, what to think of, but WPRB? I tuned the radio to 103.3 and WPRB came in clear as a bell. I could hear Rob Forman ’78 doing his broadcast. Normally, the New York stations blocked WPRB with interference, but this was unheard of! The whole New York metro area could hear. I immediately called Rob and went on the air with a live report from the blacked out area. It was a moment of glory. I still have the tape somewhere.

The Broadcasting Years

My tenure as Chief Engineer gradually wound down after my freshman year. I had to give it up for a semester when I studied abroad. I did a good bit of technical work with the crew in sophomore and subsequent years, but the purely technical interest was subsumed by my growing passion for actual broadcasting.

I started doing rock shows at odd hours during my sophomore fall semester, gradually working my way up to prime time. I’d occasionally do a jazz show as a substitute, and felt equally at home in both genres.

LISTEN: Mic breaks and news reports from Chris Fine’s jazz show on WPRB, February 29th, 1980.

I quickly learned the ins and outs of live airtime. For example, there was the critical requirement of timing songs up to the news, which fed in from the ABC network at exactly 15 minutes past the hour. It was considered bad form to fade out a song for the news, but if the song ended too soon, there was (gulp) airtime to fill with patter. There was always a Community Notebook or PSA that could be grabbed in an emergency, but otherwise, one had to improvise.

There was the matter of doing many things at once. The logs were kept on paper, generated by a monster mainframe computer program, gift of some ingenious alumnus, called LOGOL. The staff ran a batch job on punch cards every week to generate the log forms for the coming week. We would fill in the logs by hand while broadcasting. We also had to keep BMI logs of all songs played, and other paperwork. LOGOL would randomly distribute spots, PSA’s, and Community Notebooks into the mix of an hour, and would schedule station IDs. We were supposed to honor the times indicated, more or less – as long as we got them all in. While doing all of this, we had to find records in the shelves, cue them up, calculate song-set timings in our head, switch from one song to another, find various tape cartridges with pre-recorded announcements and spots on them, and watch the meters. Sometimes, records had skips in them; it was a choice of “fade out and say something,” or, very carefully, trying to bump the needle past the skipping point. Records were supposed to be re-filed in strict order after playing, and this discipline was maintained almost 100% by the staff.

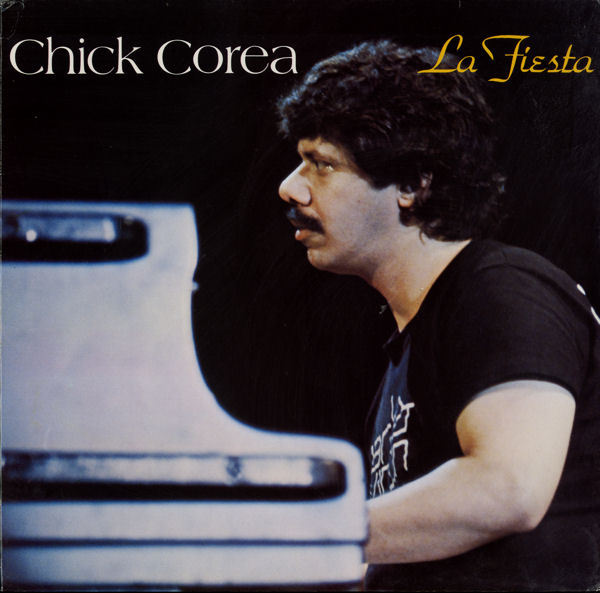

Occasionally, something electronic would blow out, or a mechanical part would fail. Audio would vanish. For these occasions, we had a large-sized tape cartridge with a recording of Chick Corea’s “La Fiesta,” and a special cartridge playback machine connected directly to the transmitter input, bypassing the console. We would jam in “La Fiesta” and frantically search for the trouble. Sometimes it was a loose wire, or a microphone problem, or the control board had to be tweaked, or turned on and off (primitive “reboot”). We would have been at the mercy of a cruel universe if “La Fiesta” had ever broken in action, as tape cartridges sometimes did when the machines ate them.

We had to read news live after each ABC feed was over. This was accomplished by “rip-and-read.” There was a Teletype machine in the room across from the studio, connected to the United Press. I would run over while a song was playing or the ABC news was on, grab some stories, and read them when ABC was finished.

The problem was, one had to learn to read ahead, and the stories needed to be quickly reviewed in advance. If one didn’t have time to pre-read the stories, how could one adhere to the informal, but sometimes-enforced, management policy of avoiding grotesque, macabre, or excessively violent stories?

One night, early in my broadcasting career, I was on the verge of running out of time. Something had distracted me while the ABC news was on, and I suddenly, frantically, remembered the local news I was supposed to read. I ran across the hall in a hurry, ripped off several feet from the roll of yellow paper scrolling out of the Teletype, and started reading. The first story I read was truly grotesque – something violent and criminal about a group of no-goods who had cruelly murdered several people. I was reading it and my mind was thinking, “Uh-oh. I’m in trouble already. What could be worse than this?” So, without reading ahead, I finished the shoot-em-up story and said, “And, on the lighter side of the news…” and launched into a second violent story that began, “A priest was murdered today in Trenton…”

1977-79 was a revolution in rock music, with the advent of punk and New Wave artists such as the Sex Pistols, The Ramones, Elvis Costello, The B-52’s, Blondie, and so many others. I started my sophomore year hating the new stuff, but by the end of that year, I loved it. WPRB not only had an extensive record collection at the time, but we got tickets to see all the good bands in various places, and some of them came to Princeton (until the Powers that Be forbade any more New Wave concerts after an unfortunate incident at a Talking Heads concert at the bathroom-challenged Alexander Hall).

Anecdote: The Phantom Carillon

WPRB staff was not above playing an occasional prank. Since the WPRB tech staff and management had the only student access to Holder Tower (through a forbidding metal door), we were often asked what was in there. The tower was bare inside except for the transmitter at the bottom, and the antenna at the top, but this mysterious Gothic structure no doubt raised questions in many people’s minds. We were more than willing to let the mystery ferment.

Relations between WPRB and the Daily Princetonian were, as least as I understand it, not always entirely cordial. Reasons for this are vague, but there was always a temptation to play a trick on the intrepid reporters of the Prince. What better way than to make up a great story?

As it happened, WPRB had a set of large, old, outdoor PA speakers, similar to the one on top of the Blues Brothers’ police car. The speakers were set up at the top of the tower, and connected to a tape recorder and amplifier. It was time for the fun to begin.

Rumors began to circulate that a wealthy alumnus had donated a bell carillon of exquisite quality and tone, which had secretly been recently installed in Holder Tower. As the rumors intensified, carillon music began to emanate from the tower. An entire story was made up about the alumnus, the gift, and the carillon itself, and given to the Prince. They planned a major feature story about the great gift. I can’t recall whether they actually published it or almost published it, but when the hoax was exposed, they were hopping mad. One or two reporters demanded to see the carillon and tried to force their way into the tower. It was at this point that we came to rely on John Williams ’80, aka “Big Oinie.” Though a gentle, kind person, and a great friend to all, John was imposingly large, and could, upon request, look threatening. He was generally the person sent round to an advertiser who was late in payment for radio spots. Oinie also had very large feet, which came in handy when the transmitter needed fixing. A good kick, and the transmitter would start to toe the line, as it were. We called this “Treatment 13-D,” after his shoe size.

The Prince staff ambushed us one night as we were going through the Holder Tower door to the transmitter room. As the reporters tried to force their way through the door, John applied Treatment 13-D to the other side, and it slammed shut. This made them even angrier, but they never found out the whole truth.

A Formative Experience Never Forgotten

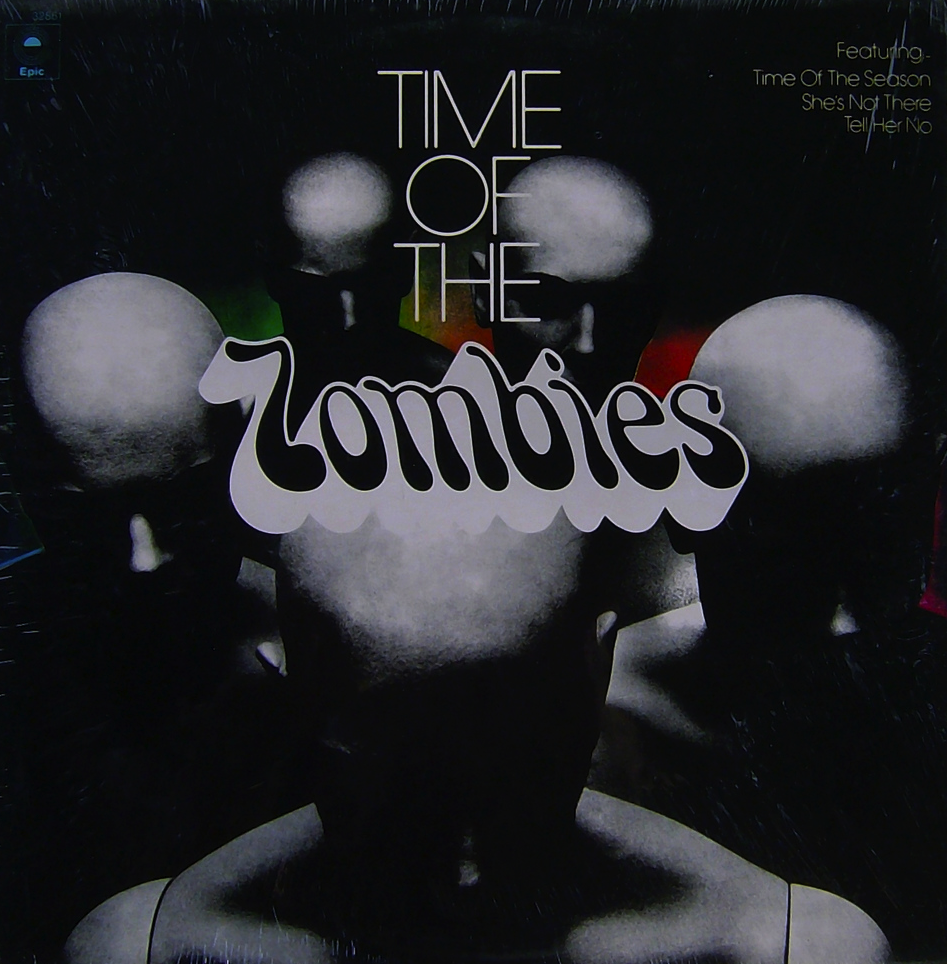

The good times at WPRB have benefited me for my entire life since. I learned about literally hundreds of artists, rock and jazz, from the WPRB record library. There was a guy named George Korval who would review every record that came in, with brief ratings of each track (“Dull!” “Best on the Album!”). It was hard to go wrong on a new, unknown album, if one followed George’s lead. There were other reviewers too, each terrific in his or her own way. I am grateful to WPRB for a lifetime of musical pleasure. In fact, just this year, I went to a concert in New York featuring the remaining original Zombies. I discovered the Zombies at WPRB, which had a copy of the only LP reissue of their material (“Time of the Zombies”) in print for many years.

WPRB led me to a lifetime of music collecting – much to the chagrin of the moving people who sometimes have had to heft my LP and tape collection when we’ve moved house. (The last ones said, at the end of the day, “Mr. Fine, why don’t you collect stamps instead?”) By senior year, in fact, my rapidly-growing LP collection took up at least half of my tiny room in New Quad. I’m not sure why I lugged them all around, but somehow, I had to have them.

WPRB cured me of mic fright. I learned to be unafraid to talk in public, and my self-consciousness at the sound of my voice disappeared. Since then, I have made many speeches in public, done webcasts, led conference calls, taught classes, etc., without fear. I owe a lifetime of these experiences to WPRB.

My thanks to Teri Noel Towe, guru of classical music and host of “Towe on Thursdays,” for reconnecting me to WPRB, after many years of memories without participation. My mother was a classical record producer who passed away in 2009. Teri said a nice thing about her on his show and I thanked him – we hadn’t met before. After that, we had a wonderful dinner together and an occasional correspondence. Finally, Teri invited me to join him as his guest on a show featuring music recorded by my parents for Mercury Living Presence. We had a fun time and it felt so good to be back on the air – particularly in the same studio with the Maestro himself. I hadn’t seen the facilities since the station was in Holder, and was quite impressed with the modern studios. Teri and I have talked occasionally about getting back together, and I look forward to it. I’ve become a loyal listener to Teri’s show.

I hope, when I retire, to get back on the air at WPRB occasionally. I’ve heard that the occasional grizzled alum can do a show, and I’m hoping that’s true. Thanks to Mike Lupica for encouraging us to submit our reminiscences and collecting our ramblings. To WPRB – thank you for all the good times, a lifetime of memories, and some of the best lessons I ever had in college.

Chris Fine ‘80